Today we spent a fair amount of time traveling, going through a variety of different ecosystems in a short period of time. We stared out in the humid lowlands of the southwest, heading northward. Along the way we stopped at the Tarcoles River, to walk across the bridge to see the American crocodiles in the shallow water below. There were about 40 of the large reptiles sunning on the sandy banks of the river below in the hot sun, with a few more slowly slithering through the murky water. The largest specimen known to occur here was 18 feet long. They congregate here in much larger numbers than normal partly because it is perfect habitat with shallow water and good basking and nesting sites, but also because they were (and maybe still are) being fed by local business owners to assure this as a stop for most tourists heading to Jaco and nearby beach towns.

American crocodiles below the bridge over the Tarcoles River (L and C) and a big croc showing its sharp teeth (R).

From there we drove up into the mountains, transitioning into tropical dry forest. The tropical dry forest includes many deciduous species, so the area can look rather desiccated when the branches are bare by the end of the six month dry season. Many of these trees produce colorful flowers, painting the hillsides in pink, yellow, orange, white, or red before the next set of leaves appear just before or at the onset of the wet season (typically in May). The buttercup trees (Cochlospermum vitifolium) were in bloom, with bright yellow flowers that look like big buttercups on the ends of leafless stems on a small upright tree, for a small splash of color among the otherwise drab vegetation. We saw some of the light pink-flowering Cassia grandis (pink shower tree) and the few broad, dome-shaped Guanacaste trees (Enterolobium cyclocarpum) that are more characteristic of the far northwest province of Costa Rica were easy to pick out by their distinctive, ear-shaped seed pods at the top of the leafless canopy.

Driving through dry tropical forest (L); a buttercup tree, Cochlospermum vitifolium (LC); pink shower tree, Cassia grandis (RC); seed pod of Guanacaste tree, Enterolobium cyclocarpum (R).

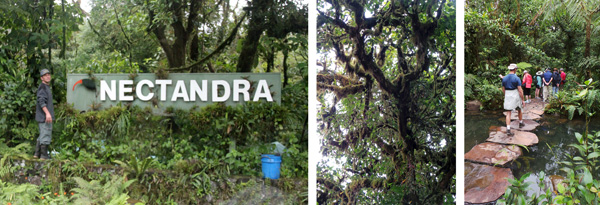

By afternoon we were in the cloud forest, an ecosystem that gets a significant amount of moisture from fog rather than rain. The plants here are adapted to being bathed in misty clouds on a regular basis, so epiphytes are numerous and the trees are usually covered with mosses, lichens, ferns, orchids, bromeliads and other plants. Tree ferns are also abundant at the higher elevations. At Nectandra Cloud Forest Garden, a private rainforest preserve with a small cultivated area that showcases plants native to their 320 acres of primary and secondary cloud forest, we learned about some of the plants that live in this unique habitat. Many of the larger trees are labeled, but none of the understory plants are, so we depended on our hosts to help identify those.

Entrance to Nectandra Cloud Forest Garden (L); epiphytes it the trees (C); walking the stone path in the cultivated area (R).

Sweetly-scented Trichophilia suavis orchids were in bloom on many of the trees (that actually live high in the trees, but when they fall onto the trails, the staff rescues them and mounts them at eye level on trees along the path). Some of the other interesting plants we encountered included a terrestrial, nocturnal-blooming orchid with yellow flowers; Philodendron malesevichiae with exceptionally furry petioles; and the palm Bactris dianeura with ferocious-looking, long, thin but very strong, black spines on the trunk that were used by early entomologists for insect pins when they ran of real pins.

Trichophilia suavis orchid (L); terrestrial orchid (LC); fuzzy petiole of Philodendron malesevichiae (RC); spines on trunk of the palm Bactris dianeura.

We also learned about bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and ferns, primarily), stopping to look at various types of those non-vascular plants. But with over 200 species of ferns there, we couldn’t cover them all. We saw a type of fern (name unknown) that only lives on the trunks of tree ferns and has both sterile fronds and different-looking fertile fronds that develop the sori. The filmy ferns have fronds that are only two layers of cells thick, so that small types look almost transparent. Up to 20 species of tiny epiphytic bryophytes (that look kind of like scummy moss) will live on a single palm leaf; they can only be distinguished microscopically.

The sterile (L) and fertile (LC) fronds of an epiphytic fern. A filmy fern (RC) and with white behind to show translucence of the fronds (R).

A little extra: some interesting tidbits on bryophytes from Kris Koch, Rotary Botanical Gardens, Janesville, WI:

Moss and lichens exhibit a property called “poikilohydry,” which means they can be significantly desiccated (90%+ water loss) and then rehydrate without physiological damage. They also rely directly on their environment for water—no cuticles or stomata to prevent them from drying out. Obviously this limits the size of the organisms if moisture is variable, but what an amazing survival strategy! Moss appears slightly more plant-like, but they have no roots, only rhizoids to help anchor them in a substrate. Both moss and lichen reproduce sexually with spores, like fungi, but they are not fungi.

Lichens are the bad boys of bryophytes. They are not quite a symbiotic relationship between a fungi and cyanobacteria. The fungi seems to hold the alga hostage to benefit from photosynthesis. The cyanobacteria do benefit from the physical structure of the fungi, but it’s not really an equal partnership. When researchers have separated the fungi from the cyanobacteria, the fungus that grows on its own is apparently nothing like a lichen. So it’s only by putting those two organisms together that the lichen can exist. Natural science is so amazing, isn’t it? One last piece of lichen trivia…scientists in Sweden have found lichens on stone that they estimate to be 9,000+ years old. Interesting that this “primitive” organism can significantly outlast we higher life forms!